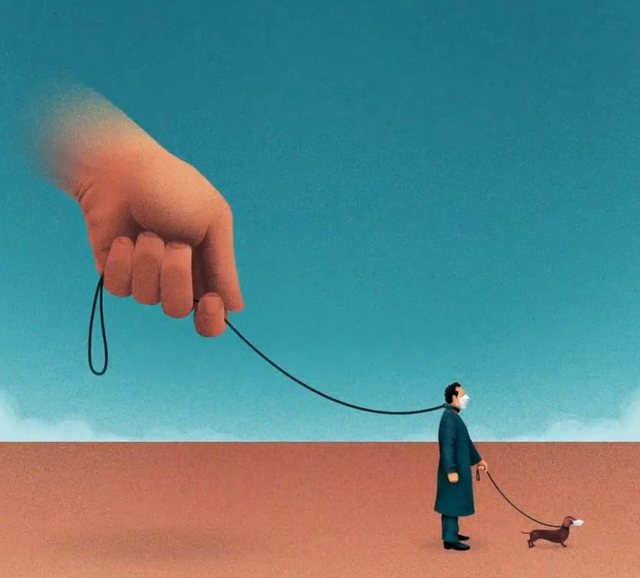

Big government is needed to fight the pandemic. What matters is how it shrinks again afterwards.

In just a few weeks, a 10,000-millimeter-wide virus has transformed Western democracies. States have closed businesses and locked people inside. They have pledged trillions of dollars to keep the economy on life support. If South Korea and Singapore are a guide, medical and electronic privacy will be cast aside. It is the most dramatic extension of state power since World War II.

Taboos are breaking down one after another. Not only through the threat of fines or imprisonment for the common people who do ordinary things, but also the size and scope of the government's role in the economy. In America, Congress is ready to pass a package worth nearly $ 2trn, 10% of GDP, twice as much as promised in 2007-09. Credit guarantees from Britain, France and other countries are worth 15% of GDP.

Central banks are printing money and using it to buy assets they once rejected. For a while, at least, governments have been seeking to stop bankruptcy.

For those who believe in limited government and open markets, Covid-19 is a problem. The state must act decisively. But history suggests that after the crisis, the state does not give up all of its bases. Today this has implications not only for the economy but also for the supervision of individuals.

It is no coincidence that the state grows during crises. Governments may have stumbled upon the pandemic, but they can only force and mobilize large resources rapidly. Today they are needed to enforce business closure and isolation to stop the virus. Only they can help offset the resulting economic collapse. In America and Europe, GDP can fall by 5-10% year-on-year. Probably more.

One reason that the role of the state has changed so rapidly is that Covid-19 spreads like wildfire. In less than four months it has passed from a market in Wuhan to almost every country in the world. Last week it registered 253,000 new cases. People fear the example of Italy, where almost 74,000 registered cases have overtaken a world-class health system, leading to over 7,500 deaths.

This fear is the other reason for rapid change. When Britain's government tried to come down in order to minimize state intervention, it was accused of doing too little and responding late. In contrast to Britain, France passed a law this week giving the government the power not only to control people's movements but also to manage prices and stocks of goods. During the crisis, its president, Emmanuel Macron, has seen his approval ratings rise.

In much of the world the state has so far responded to Covid-19 with a mixture of coercion and economic pressure. As the pandemic persists, they will likely harness its unique power to monitor people using their data.

Hong Kong uses apps on phones that show "where you are applying the quarantine". China has a passport system to record who is safe to go out. Phone data helps modelers predict the spread of the disease. If a government (let's stop) the development of Covid-19, as China has done, it will have to prevent a second wave among many who are still sensitive, raising the voice for any new grouping. South Korea says that automatically tracking contacts for fresh infections, using cellular technology, results in ten minutes instead of 24 hours.

This huge increase in state power has happened so fast that there is almost no time for debate. Some will assure themselves that it is merely temporary and that it will leave no trace, as with the Spanish flu a century ago. However, the response rate makes Covid-19 more like a war or Depression. And the data here suggests that crises lead to a greater state forever, with a lot of power, as well as responsibilities and taxes to pay for it. The welfare state, income tax, nationalization, all grew out of con kon ict and crisis.

Some of today's changes will be desirable. It would be great if governments were better prepared for the next pandemic; if they invested in public health, including in America, where reform is sorely needed. Some other countries need a good salary for sick people.

Other changes may be less clear, but they will be difficult to shift because they were supported by powerful constituencies even before the pandemic. One example is the further choice of the euro area pact that is supposed to impose discipline on lending to member states. Likewise, Britain has taken its railways under state control, a step that is supposed to be temporary but can never be withdrawn.

Most worrisome is the spread of bad habits. Governments can be drawn into autarchy (a country or society that is economically independent). Some fear that the ingredients for medicines will run out, many in China. Russia has imposed a temporary ban on wheat exports. Industrialists and politicians have lost faith in supply chains. The trade prospects are already dim. In the long run, a broad and steady expansion of the state along with dramatically higher public debt is likely to lead to a kind of rigid, less dynamic capitalism.

But this is not the biggest problem. The biggest concerns lie elsewhere, in abuse of office and threats to freedom. Some politicians are already seizing power, like in Hungary, where the government is seeking an indefinite state of emergency. Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu appears to view the crisis as a chance to avoid a corruption trial.

Most worrying is the distribution of interventional surveillance. Invasive data collection and processing will be widespread because it offers a real advantage in disease management. But they also demand that the state have routine access to citizens' medical and electronic records. The temptation will be to use post-pandemic surveillance as much as anti-terror legislation was chosen after 9/11. This can start with finding drug dealers. No one knows where it would end up, especially if, dealing with Covid-19, China overseen crazy, seen as a model.

Surveillance may be necessary to withstand Covid-19. Rules with current clauses and integrated scrutiny can help stop it at that time. But the main defense against the dominant state, in technology and economics, will be the citizens themselves. They need to understand that a pandemic government is not suitable for everyday life.