For the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428–347 BC), in Book 10 of the Republic, art is a mimesis – an imitation. But since art (especially painting) is a copy and not something real, Plato did not consider it useful. One cannot smoke an image of a pipe or sleep in an imaginary bed. (He did not discuss architecture, which is typically useful.)

Plato's term techne refers to a person's technique or ability to create something useful, something real, distinguishing this ability as a form of art. He believed in the existence of a world of ideas that is boundless and unchanging according to the form of things that exist in the physical world. The "real" bed is the form that exists without limit; the bed you sleep on is a copy or example of the real bed. A painted bed is much further from the truth than the real bed, and, according to Plato, this is dangerous because of the great distance between the imaginary and the real.

In 1928, the Belgian artist René Magritte painted one of his most famous works, The Betrayal of Images, which clearly represents Plato's argument. At first glance, it is a representative, straightforward, and believable image of a pipe. However, beneath the image, Magritte has written "This is not a pipe" (Ceci n'est pas une pipe), to remind the viewer that what is being painted is not real and that art and reality are separated by a whole space. The "betrayal" in Magritte's title is consistent with Plato's notion that such an image can be dangerous.

For Plato, essential truth and beauty lie only in the spectrum of ideas, and works of art pose a danger to society. Since art (along with poetry and music) can arouse dangerous passions in man, Plato banished artists, poets, and musicians (although he permitted musical material) from his Republic.

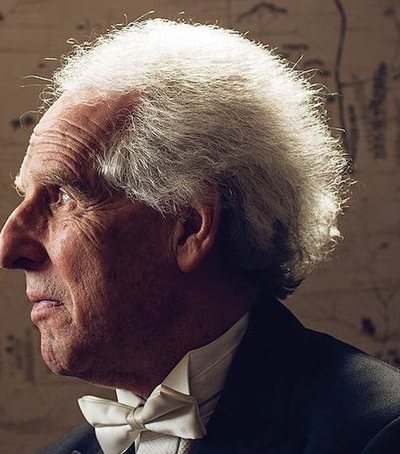

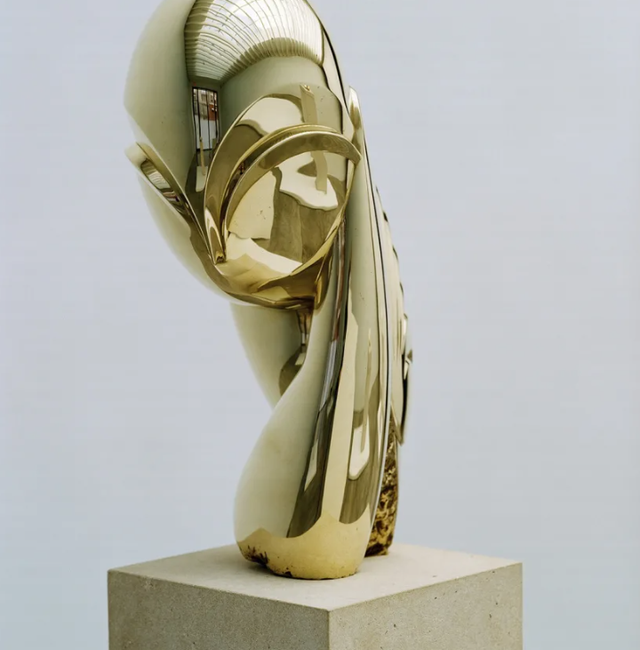

The early 20th-century Romanian artist Constantin Brâncu?i believed that his sculptures represented the “essence of things” – an approach consistent with Plato’s ideal forms, although Brâncu?i may not have been necessarily influenced by him. For example, his 1912 marble sculpture Mlle. Pogany was, according to him, the essence of the Hungarian woman Margit Pogany, whom he met in Paris and whose image he cast in bronze and marble. Brâncu?ie severed the body from her hands and presented Mlle. Pogany with her arms clasped around her neck. He emphasized her large eyes, giving her a thin nose and lips. To some viewers, Brâncu?i was an “abstract” artist, but he thought that some of them were simply incapable of understanding the truths of his images.

Art as a form

Në Poetikën e tij, studenti i Platonit, Aristoteli (384–322 p.K.), identifikoi formën si cilësinë sipas së cilës shikuesi i përgjigjet një vepre arti pamor. Forma, sipas tij, prodhohet nga kontrolli i materialit nga ana e artistit dhe nga aftësia e tij për të kapur thelbin e gjërave – në mënyrë të ngjashme me synimin e Brâncu?it.

Ndryshe nga Platoni, për Aristotelin, thelbi i gjërave është brenda tyre dhe mund të paraqitet nëpërmjet materialit, formës dhe aftësive teknike (techne) të artistit. Kështu, nuk ka humbje nga realja tek përfaqësimi artistik dhe as rreziqe siç i shihte Platoni. Për Platonin, thelbi ekziston vetëm në botën e ideve dhe është i pavarur nga gjërat.

Për secilin filozof – Platonin, idealist, dhe Aristotelin, empirik – paragjykimet e tyre formojnë këndvështrimet mbi artin. Aristoteli mendonte se madhësia e një imazhi duhet të jetë e përshtatshme, duke paraqitur një sens bashkësie dhe tërësie, në mënyrë që shikuesi t’i përgjigjet rëndësisë së formës së përsosur gjeometrike. Një figurë nuk duhet të jetë shumë e vogël, që të kuptohet lehtësisht, as shumë e madhe, që të mos mund të shihet si një e tërë.

Sipas tij, pjesët e çdo figure duhet të jenë proporcionale dhe simetrike. Një vepër e mirë arti është e aftë të japë njohuri dhe të zgjerojë përvojën e të kuptuarit të botës natyrore. Sa më shumë që një vepër të jetë imitim bindës i diçkaje reale, aq më shumë kënaq shikuesin. Ky këndvështrim konfirmohet nga reagimi popullor ndaj disa veprave të fotorealizmit dhe hiperrealizmit të gjysmës së dytë të shekullit XX, figura që duken po aq reale sa në jetën e përditshme.

Arti si objekt

Filozofi gjerman i shekullit XVIII, Immanuel Kant, në veprën e tij Kritika e gjykimit (1790), shkroi se, për t’u kualifikuar si një vepër arti, një imazh duhet të jetë i pajisur me fuqinë imagjinare të artistit dhe, njëkohësisht, të provokojë një përgjigje imagjinative nga shikuesi, duke krijuar një lloj “dialogu” harmonik mes tyre.

Ashtu si Platoni dhe Aristoteli, Kanti fliste për artin figurativ me një temë subjektive të dallueshme. Por ai vlerësonte edhe nëse një vepër arti ishte “e bukur”, një cilësi që e shihte të varur nga gjenialiteti i artistit. Ai besonte se arti kishte dimension moral dhe nivele estetike të kuptimit që stimulojnë mendjen, të jenë origjinale dhe të përmbajnë shpirtin e gjeniut – diçka që nuk e ofron natyra.

Kant bëri dallimin mes “arteve të bukura”, që kanë ide shprehëse dhe cilësi morale, dhe “arteve që kënaqin”, të cilat mund të jenë argëtuese e dekorative, por pa përmbajtje të thellë. Një vepër e mirë arti, sipas tij, arrin një sintezë harmonike mes formës dhe përmbajtjes.

Për Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), qëllimi kryesor i artit ishte zgjerimi i njohurive për veten dhe kuptimi i botës. Ai i jepte rëndësi kontekstit historik dhe realitetit fizik të materialit të artit. Një vepër arti, sipas Hegelit, nuk ka vetëm estetikë dhe shpirt, por është edhe një artefakt që pasqyron periudhën historike dhe kulturën e saj.

Hegel identified three main historical periods of the development of art:

1. Ancient Egypt, which he called Symbolic.

2. Greece of the 4th century BC

3. The Christian period.

According to him, the Greeks produced the most spiritual and physically harmonious art, especially in sculpture.