Message 1

Many of you may know the story of two merchants who traveled to Africa in 1900. They were sent to find out if there was any opportunity to sell shoes there. Both sent telegrams back to Manchester. One wrote: “The situation is hopeless. They don’t wear shoes.” While the other wrote: “Extraordinary opportunity; they still don’t have shoes.”

The same situation, according to Zander, exists in the world of classical music. There are those who think that classical music is dying, but there are also those who think that “you haven’t seen anything yet.”

Message 2

I believe there are about 160 of you here. I would say that maybe 45 of you are absolutely passionate about classical music. You adore it: your radio is always tuned to the classical channel, you have classical CDs in your car, you go to the symphony, you might even have children who play instruments. You can't imagine your life without it. This is the first group – a small but dedicated group.

The second group is larger. They are the ones who have no problem with classical music. After a long day, they come home, have a glass of wine, put their feet up on the table and put some Vivaldi in the background. And that's nice.

The third group consists of those who never listen to classical music. It's simply not part of their lives. They might hear it by chance at the airport or a fragment from "Aida," and that's it. This is the largest group.

Then there is the fourth group, a small one: those who think they have no ear for music. But, according to Zander, no one is truly “deaf” to music. We distinguish tones: the gearshift of a car, the dialect of a person from Texas compared to someone from Rome, or the voice of our mother when she calls us. We all have a “fantastic ear.”

Message 3

Now I will play you a wonderful piece by Chopin, Prelude No. 4. Before you play it, imagine someone who is no longer with you – a beloved grandmother, a friend, someone you loved very much – and hold that person in your mind as you follow each note to the end. Then you will hear everything Chopin has to say to you.

Ten years ago, Zander was in Ireland during the Troubles, working with Catholic and Protestant children on conflict resolution. He played them this piece by Chopin. The next day, one of the boys, who had never heard classical music, said to him,

“My brother was shot last year, and I didn’t cry for him. But last night, when you played that piece, I was thinking about him, and tears came down my face. And it felt good to be able to cry.”

In that moment, Zander realized that classical music is for everyone.

Message 4

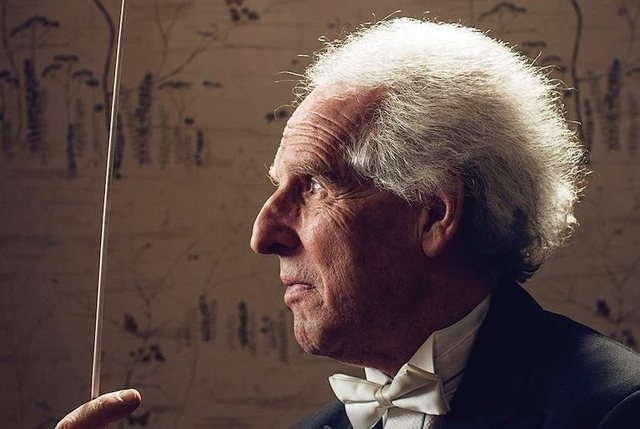

When I was 45 years old and had been conducting for 20 years, I suddenly realized something fundamental: the conductor of an orchestra does not produce any sound. He depends for his power on the ability to make others powerful. This understanding changed my life.

My job, says Zander, is to awaken possibilities in people. And the way to know if you've achieved that is to look into their eyes. If their eyes are shining, then you're successful. If not, the question you need to ask is: "What am I doing that their eyes aren't shining?"

We can apply this to our children as well. Success, he says, is not about fame or fortune, but about how many "shining eyes" we have around us.

Message 5

The words we say matter a lot. Zander learned this lesson from a woman who survived Auschwitz. She was 15 when she left for the camp, and her brother was 8. On the train, she spoke harshly to her younger brother who had lost his shoes. Unfortunately, he did not survive, and she never saw him again.

After the war, she made an oath: “I will never say anything to anyone that would not have the weight of the last thing you could say to someone in your life.”

Benjamin Zander (1939) is an English conductor, currently principal conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, as well as a guest conductor with orchestras worldwide. He is completing a recording of the complete cycle of Mahler's symphonies, which has received exceptional acclaim, both for his interpretation and for the explanatory material that offers listeners a deeper understanding of the music.

Source: TED Talk