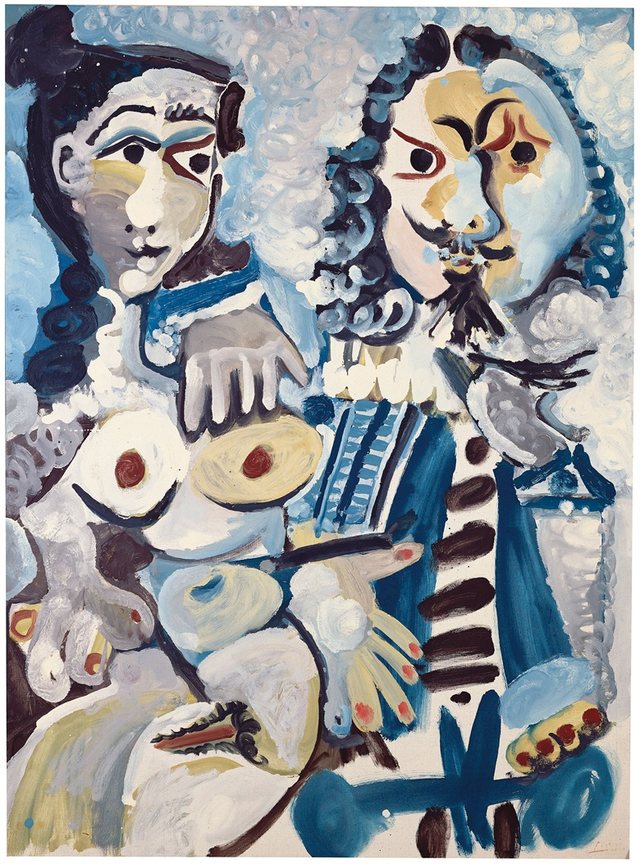

Later in life, Picasso represented himself in his art under the guise of adventurous and virile musketeers. Perhaps nowhere is this better illustrated than in his masterpiece, the painting “Mousquetaire et nu assis.”

Executed with luxurious and passionate brushstrokes, the painting "Mousquetaire et nu assis" is among the first triumphant depictions of musketeers to appear in Pablo Picasso's work in 1967.

Accompanying this iconic figure is a seated nude with dark hair and large, all-seeing eyes. This is Jacqueline, Picasso's last great love, muse, and wife, whose presence permeates every painted female figure in the final chapter of Picasso's life.

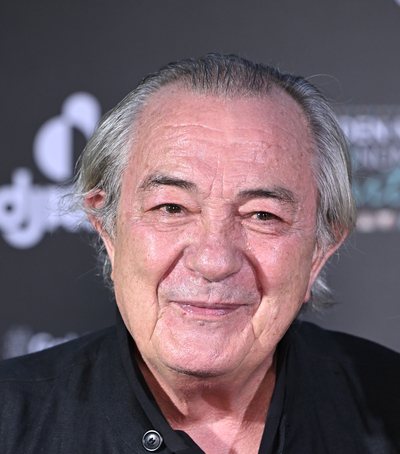

'Picasso's later career was defined by sensual paintings in which he presents himself as a virile artist in the arms of his voluptuous lover,' explains Keith Gill of Christie's, London. With one eye towards the Old Masters and another towards contemporary art, the painting "Mousquetaire et nu assis" shows Picasso "plundering" the past in a remarkably fresh and gestural way.

Like Titian, Rembrandt, Matisse or de Kooning, Picasso produced an extraordinary number of paintings and drawings in his final years. 'He seemed to have a sense of urgency in his works from this period, as if he were trying to beat the passage of time,' says Gill.

Throughout his career, Picasso often drew historical, classical, or mythological 'types': he variously imagined himself in his art as a melancholic harlequin, as a monstrous minotaur, or as a courageous bullfighter.

Above all, what radiates in his later work is desire.

The figure of the musketeer first appeared in Picasso’s work towards the end of 1966, just a few months before he painted “Mousquetaire et nu assis.” While recovering from surgery at his home in Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Mougins, France, he immersed himself in literature, devouring the plays of Shakespeare and the novels of Balzac, Dickens, and Dumas. When Picasso began painting again in the spring of 1967, it was the characters of Dumas’ “The Three Musketeers” leaping off the page and into new life on the canvas.

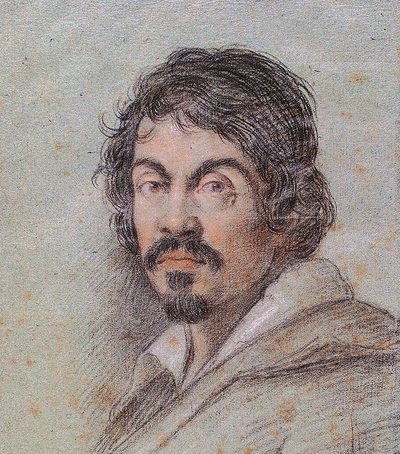

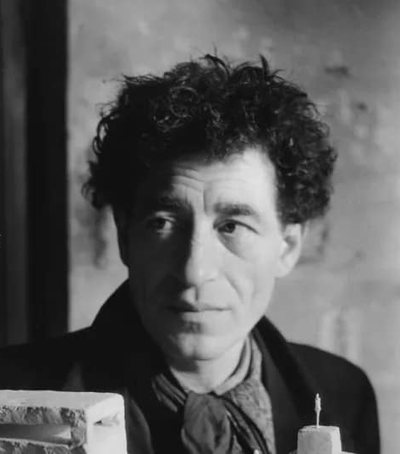

The figure of the musketeer had a long history in the visual arts, too, represented in the works of Hals, Rembrandt, El Greco, Velázquez, and Goya. In referencing venerable artists of the past, Picasso was measuring himself against them, while he was appreciating that he belonged to the lineage of the great masters.

‘Why did Picasso lock horns with the great painters one after another?’ asked John Richardson in a 1984 article for The New York Book Review. ‘Was it a show of strength—an arm-wrestling? Was it for the sake of mockery or ridicule, irony or homage, Oedipal rivalry or Spanish chauvinism? Each case is different, but there is always an element of identification, an element of cannibalism involved—two elements which, as Freud has shown us, are part of the same process. Indeed, Freud described this process of identification as “psychic cannibalism.” You identify with someone; you cannibalize them; you assume their power. How accurately that described what Picasso was dealing with in his later years.’

More than anyone else in this pantheon of artistic heroes, it was Rembrandt's work that he identified with, or 'cannibalized', in his creation of the Musketeers. Yet the speed with which he painted was reminiscent of the Abstract Expressionists. 'When things were going well,' Jacqueline once recalled, 'He would come down from the studio saying, "They're coming! They're coming, aren't they?"'

Above all, what radiates in Picasso's later works is desire: both sexual desire and the desire to paint without content, without thought, without obstacles. This desire, and the thirst for life of an artist very aware of his aging, charges the painting "Mousquetaire et nu assis" with its vivid and immediate power.

Painting, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), "Mousquetaire et nu assis", 1967.